Taking away the toll

Its cure rates are incredible, but at a cost: chemotherapy at doses so toxic they could kill, if not delivered with the proper supportive care.

Lisa Roth, M.D., is hoping to change the course of care for children and young adults with Burkitt lymphoma, an aggressive disease that is relatively rare in the United States, but among the most common pediatric cancers elsewhere in the world.

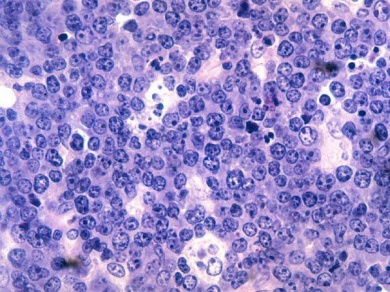

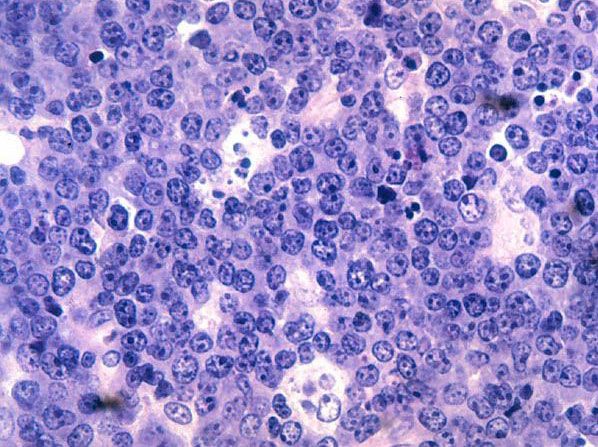

Burkitt lymphoma is a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in which cancer starts in immune cells called B-cells. It is rapidly fatal if left untreated.

As many as 85 percent of children with Burkitt lymphoma respond well to treatment. Their tumors grow incredibly fast – doubling in size in a matter of days – but also shrink incredibly fast when blasted with high-dose chemotherapy. In order to ensure the tumors don’t return, they undergo intensive sustained treatment that generally lasts from 4-8 months.

For those who don’t respond, however, or for those whose disease returns despite the treatment, the survival rate is below 20 percent. And success is often tempered by immediate and long-term side effects, including cardiovascular problems, infertility and secondary malignancies.

“We do very well, curing the majority of patients; the problem is the amount of chemotherapy needed to get to that cure rate is substantial,” Roth said. “As our patients are surviving longer and longer, we are beginning to see the toll the treatments are taking long-term.”

Roth - the Charles, Lillian, and Betty Neuwirth Clinical Scholar in Pediatric Oncology - recently received funding from the St. Baldrick’s Foundation to investigate a promising new drug, PU-H71, which kills Burkitt lymphoma by attacking a protein (Heat Shock Protein 90 – Hsp90) that the tumor needs to survive.

The targeted therapy would kill cancer cells and spare healthy cells, with much less toxicity than chemotherapy, and offer an option for those whose tumors do not respond to current treatments.

Far-reaching Impact

This would be great news for Roth’s patients, but its implications would be even more substantial an ocean away, in Africa, where incidence of Burkitt lymphoma is much higher and cure rates much lower.

Many children in sub-Saharan Africa are afflicted with a form of Burkitt lymphoma associated with the Epstein Barr virus. At Weill Bugando University College of Health Sciences/Bugando Medical Centre in Mwanza, Tanzania, where Roth visited as a resident, there is an entire ward dedicated to the disease.

A lack of supportive care means children cannot receive the high-dose chemotherapy regimen given in the US, or their family circumstances do not permit sustained treatment. As a result, survival rates in Africa hover around 40 percent.

“Burkitt lymphoma is a major health concern in Sub-saharan Africa, and outcomes for those children are poor,” Roth said. “They would particularly benefit from targeted therapies.”

Roth is working with the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Global Health on a new pediatric Burkitt lymphoma trial network to develop clinical trials in in resource-limited countries in Africa and South America. And she is studying the biology of the different subtypes of the disease to elucidate differences that may be clinically relevant.

“There are likely biologic differences between tumors that develop in the U.S. and Africa. We are working to determine if these differences may impact therapy; at this time we really don’t know,” Roth said.

She is also trying to unravel the mystery of why Burkitt lymphoma tumors are so chemosensitive when first presented, yet so chemoresistant when relapsed.

“No one has looked at the genetics of relapsed tumors compared with the original tumors,” Roth said.

In partnership with the Englander Institute of Precision Medicine, Roth is setting out to do just that, investigating the genomic evolution of paired specimens of Burkitt lymphoma tumors. She is comparing tumors at the time of initial diagnosis to tumors that develop at the time of relapse to understand what has changed.

The hope is that PU-H71 will be effective across the spectrum of Burkitt lymphoma subtypes and in relapsed tumors, and initial results are promising.

“The protein Hsp90 has a lot of different functions in the cell, and is required by a lot of pathways. This makes it an attractive drug target which may be relevant across a range of patients regardless of specific genetic alterations,” Roth said.

Her team has shown that PU-H71 effectively kills Burkitt lymphoma cells at low doses, and they are now expanding testing to other models of the disease. Roth is working with Giorgio Inghirami, M.D., professor of pathology and laboratory medicine; Ari Melnick, M.D., the Gebroe Professor of Hematology/Oncology; Leandro Cerchetti, M.D., assistant professor of medicine; and other colleagues at the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center to implant patient-derived tumor samples (xenografts) in mice, for example.

“We want to better understand how PU-H71 works and which patients are most likely to respond to treatment. This will help us select candidates for clinical trials, which is our ultimate goal,” Roth said.

Given the aggressiveness of the disease and the speed at which it progresses, Roth said doctors will want to be very careful when choosing treatments for their young patients.

“You often don’t have a second chance,” she said.

Lost between two worlds

In addition to her Burkitt lymphoma work, Roth is building an adolescent and young adult lymphoma program, to cater to a population that don’t always fit neatly into either the pediatric or adult wards.

“Diagnostically and clinically, they can get a little lost between the two worlds,” Roth said.

Roth said the program will address some of the particular needs of the young adult population, such as fertility or school/job retention.

It will also attempt to tackle another need: research.

“The field has really stagnated in young adult lymphoma, where there haven’t been the advances that we see in childhood cancer,” Roth said. “There are not many clinical trials aimed at this age range; we would like to enroll more adolescents in clinical trials, and to create some specifically for them.”

Roth’s research will be presented Dec. 7 at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) in Orlando, Fla.