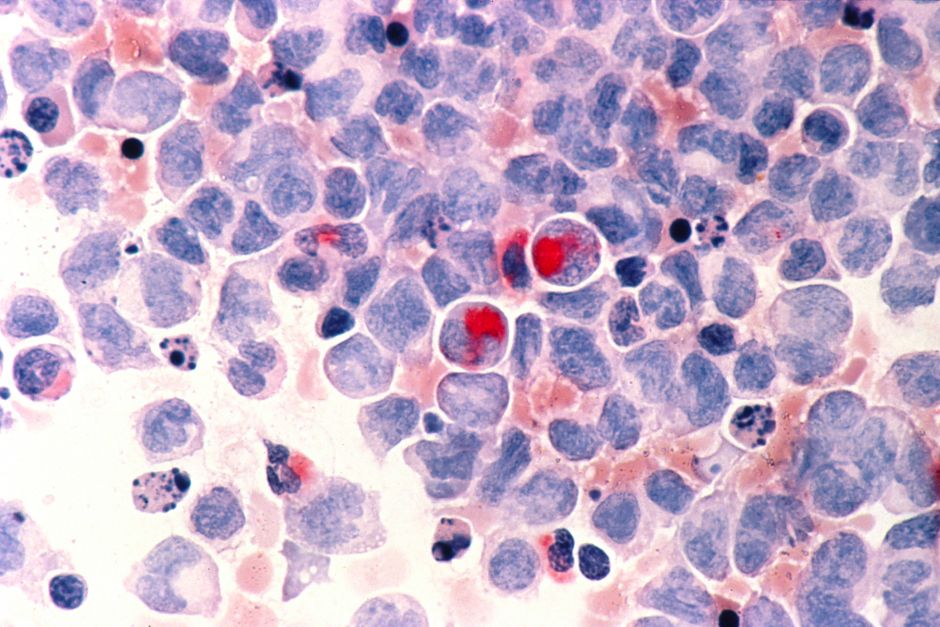

Roboz discusses progress, challenges in AML

When Gail J. Roboz, M.D., took the stage Wednesday to give her talk on what’s ahead in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), she admitted feeling a little jealousy toward her colleagues in the lymphoid diseases.

“AML continues to languish at the bottom of the survival curve. The lymphoid diseases are just doing so much better,” said Roboz, associate professor of medicine and director of the Leukemia Program at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University and the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital.

That is not to say, however, that research into myeloid diseases is “completely languishing,” Roboz stressed in her presentation at the 2014 Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium. Real progress has been achieved in understanding AML’s biology, and new targeted agents are being explored to improve outcomes.

For example, Roboz noted, mutations in FLT-3 (FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3) are associated with highly proliferative leukemia and adverse outcomes, while mutations in NPM1 (nucleophosmin 1) and biallelic mutations in CEBPA (CCAAT enhancer-binding protein a) have significantly more favorable survival.

“Although the mechanism of action of AML is much better understood, it’s not simple, and that’s the problem,” Roboz stressed.

Another challenge in treating patients with AML—which Roboz noted results in 10,000 deaths of the approximately 13,000 cases diagnosed each year—is whether more cases will be diagnosed, as patients survive other cancers. “We know that it’s associated with chemo and radiation exposure,” as well as other known environmental risk factors, genetic abnormalities, and benign and hematologic diseases also associated with AML.

Improving on Standard of Care

Although the current cytarabine-based 7+3 regimen remains the standard of care, “we do understand our weapon a little better, and this has certainly resulted in some survival benefit,” said Roboz, adding that this “much-worked-on regimen can be given to much older patients.”

Roboz, who will be leading an AML education session at the American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting in San Francisco next month, reviewed successive efforts by the German AML Study Group “to make chemo better,” through variations on (and additions to) the 7+3 dosing regimen, but these have led to what she described as “superimposable curves.”

“Is it in fact a triumph of hope over experience to add things on to 7+3?” This is a useful question, she elaborated, because “is it that we’re adding new things that aren’t new enough or are we adding them in the wrong place? It’s certainly concerning that all of these efforts over all of these years led to superimposable graphs.”

Other agents are pending, said Roboz, including clofarabine which, she said, “definitely works in AML, but we can’t quite get it right to be where it needs to be an approved drug for AML. We’re anxiously awaiting whether it can ‘beat’ 7+3,” she said.

A phase II study of CPX-351,1 which, Roboz explained, “is taking 7+3 and trying to make it better. This is a formulation that holds cytarabine and daunorubicin in a fixed 5:1 ratio, and we’re waiting to see whether what looked like a benefit in overall survival in a very difficult-to-treat population of secondary AML patients will hold up in a randomized trial, and whether taking the best regimen that we have and making the formulation better will get the job done.”

Roboz also hopes to have data available soon from the multicenter Alliance trial, looking at decitabine versus decitabine plus bortezomib in a 10-day schedule.

Looking ahead, said Roboz, “We have epigenetics, we have targeted therapies, personalized medicine. We must be on the way to improved therapeutic options.”

“Hope springs eternal. We want these agents to work and to synergize with our ‘best regimens,’” she said.

This article first appeared at OncLive.