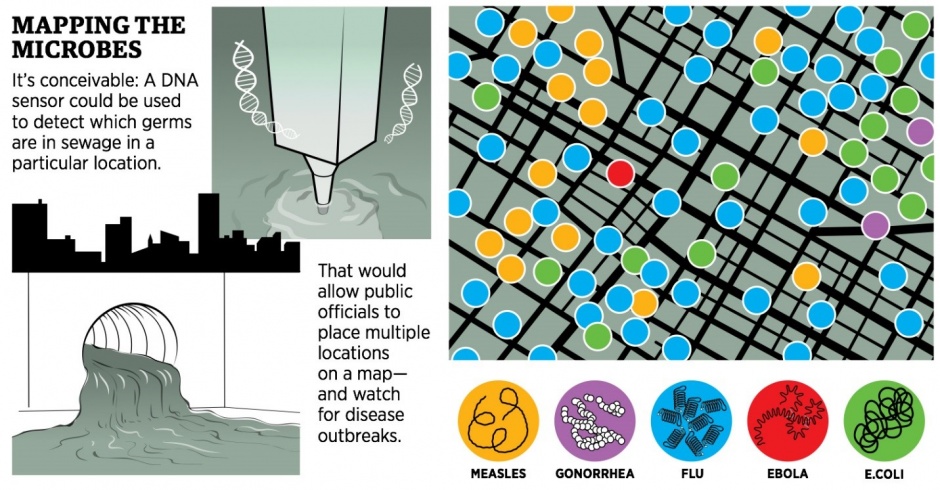

How DNA sequencing in sewers could detect disease outbreaks

Disease prevention and mapmaking have been inextricably intertwined since 1854, when an English physician named John Snow plotted a cholera outbreak on a grid to locate–and shut down–a bacteria-tainted water pump, inventing the modern science of epidemiology along the way.

In 2010 geneticist Eric Schadt, then the chief scientific officer at DNA sequencer maker Pacific Biosciences, had a brainstorm as to how to update Snow’s breakthrough for the modern age. The germs that infect us–everything from influenza to measles to bubonic plague–wind up in our waste. Why not look for them by using DNA technology to sequence raw sewage?

Snippets of DNA in wastewater could then be matched to known pathogens–and specific physical locations. Public health officials would no longer have to wait for someone to spike a fever to know that Ebola virus was in Manhattan–they would be alerted by the sequences coming from the sewers, and they would know within a few blocks where it was.

Schadt tried the project out using samples from the San Francisco sewers, but bringing sewage back to PacBio’s expensive, heavy sequencers was impractical at best. Christopher Mason, a Weill Cornell Medical College professor, has picked up a simpler version of the idea, applying swabs to surfaces all over New York City to create a “Pathomap” of germs that will be unveiled early next year.

But Schadt, who now heads a sweeping Carl Icahn-funded genomics effort at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in Manhattan, still wants a more detailed map produced automatically from sewage. Possible? One new DNA sequencer, made by Oxford Nanopore, is a thumb drive that can take sequences on the spot. Who knows what another generation of innovation could bring? Says Mason: “It’s futuristic, but not unrealistic.”

This story appears in the December 29, 2014 issue of Forbes.