Big Data and Bacteria: Mapping the New York Subway’s DNA

News outlets around the world were abuzz with reports about Weill Cornell researcher (and Meyer Cancer Center member) Christopher Mason's PathoMap Project. Here's an excerpt from the original Wall Street Journal feature, followed by an assortment of coverage in other outlets.

Aboard a No. 6 local train in Manhattan, Weill Cornell researcher Christopher Mason patiently rubbed a nylon swab back and forth along a metal handrail, collecting DNA in an effort to identify the bacteria in the New York City subway.

In 18 months of scouring the entire system, he has found germs that can cause bubonic plague uptown, meningitis in midtown, stomach trouble in the financial district and antibiotic-resistant infections throughout the boroughs.

Frequently, he and his team also found bacteria that keep the city livable, by sopping up hazardous chemicals or digesting toxic waste. They could even track the trail of bacteria created by the city’s taste for pizza—identifying microbes associated with cheese and sausage at scores of subway stops.

The big-data project, the first genetic profile of a metropolitan transit system, is in many ways “a mirror of the people themselves who ride the subway,” said Dr. Mason, a geneticist at the Weill Cornell Medical College.

It is also a revealing glimpse into the future of public health.

Across the country, researchers are combining microbiology, genomics and population genetics on a massive scale to identify the micro-organisms in the buildings and confined spaces of entire cities.

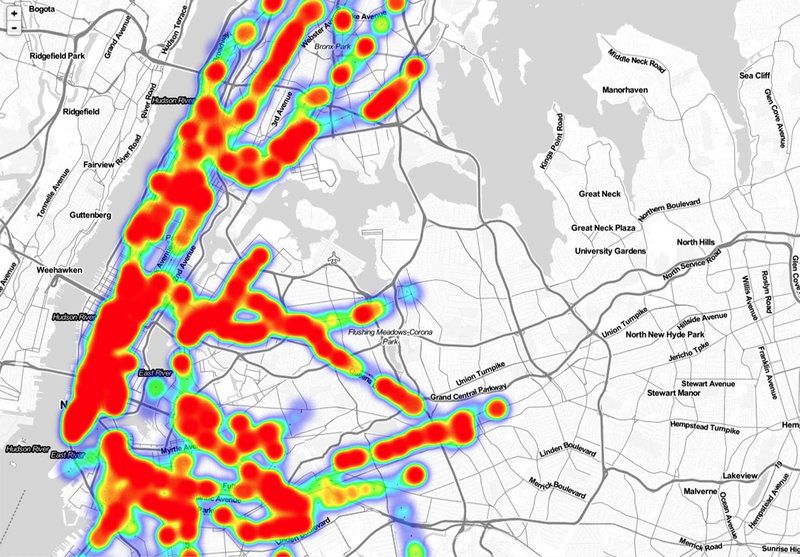

Click on the map for a station-by-station look at the bacteria found by the scientists. Above, stations where bacteria related to sepsis were identified.By documenting the miniature wildlife, microbiologists hope to discover new ways to track disease outbreaks—including contagious diseases like Ebola or measles—detect bioterrorism attacks and combat the growing antibiotic resistance among microbes, which causes about 1.7 million hospital infections every year.

“We know next to nothing about the ecology of urban environments,” said evolutionary biologist Jonathan Eisen at the University of California at Davis. “How will we know if there is something abnormal if we don’t know what normal is?”

Dr. Mason and his research team gathered DNA from turnstiles, ticket kiosks, railings and benches in a transit system shared by 5.5 million riders every day. They sequenced the genetic material they found at the subway’s 466 open stations—more than 10 billion fragments of biochemical code—and sorted it by supercomputer. They compared the results to genetic databases of known bacteria, viruses and other life forms to identify these all-but-invisible fellow travelers.

In the process, they uncovered how commuters seed the city subways every day with bacteria from the food they eat, the pets or plants they keep, and their shoes, trash, sneezes and unwashed hands. The team detected signs of 15,152 types of life-forms. Almost half of the DNA belonged to bacteria—most of them harmless; the scientists said the levels of bacteria they detected pose no public-health problem. Data from the PathoMap Project, as Dr. Mason calls it, was published online in the journal Cell Systems on Thursday.

....

No two subway stations were exactly the same, said Weill Cornell project leader Ebrahim Afshinnekoo, who helped analyze the data.

The greatest subway biodiversity was found at the Myrtle-Willoughby Avenue stop for the G train in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, where 95 unique bacteria groups were detected.

The most unusual bacteria inhabit the South Ferry Station, which has been closed since it was flooded during superstorm Sandy in 2012. “We saw bacteria there that previously were only seen in Antarctica,” Dr. Mason said.

Among the DNA of higher organisms, the researchers found across the system that genetic material from beetles and flies was the most prevalent—the cockroach genome hasn’t been sequenced yet so that DNA wasn’t identified. Cucumber DNA ranked third—possibly from lunch leftovers, or from the computer grouping partial DNA from other plants into the nearest known species.

Human DNA ranked fourth. The genetic leavings of mice, fish and lice were commonplace. (The fish DNA is likely swept in on the 14 million gallons of water that city crews pump out of the subways every day.) In some stations, about 15% of that higher order DNA belonged to rats.

So far, scientists have identified 562 species of bacteria, most of them benign or low risk. At least 67 of those species can make people sick. Even these infectious bacteria were all detected at such low levels that they were unlikely to cause illness in a healthy person.

Among the pathogenic and infectious bacteria, the Cornell researchers identified DNA related to strep infections at 66 stations and urinary tract infections at 192 stations. They found E. coli at 56 stations and other bacteria related to food poisoning at 215 stations.

A multidrug resistant bacterium called Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, associated with respiratory ailments and hospital infections, turned up at 409 stations. Another antibiotic resistant infectious microbe, called Acinetobacter baumannii, turned up at 220 stations.

At spots in three stations—on a garbage can, a MetroCard vending machine and a stairway railing—they also turned up traces of the bacteria that cause bubonic plague. While common among rodents in the western U.S., plague infections are extremely rare along the Eastern Seaboard. It has been 12 years since a human case has been diagnosed in New York City, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We think the rats are the likely carrier [of the plague bacteria], since we see plenty of rat and mouse DNA,” said Dr. Mason.

They also found a trace of anthrax DNA on a railing at one station and on a handhold in a subway car. “The results do not suggest that the plague or anthrax is prevalent, nor do they suggest that NYC residents are at risk,” the researchers reported.

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene “strongly” disputed that the bacteria were correctly identified. “The interpretation of the results are flawed, and the researchers failed to offer alternative, much more plausible explanations for their findings,” a department spokeswoman said in a written statement. “The NYC subway system is not a source of plague or anthrax disease, and the bacteria that cause these diseases do not occur naturally in this part of North America.”

The subway DNA was also a measure of urban appetites.

The scientists detected DNA from bacteria associated with the production of mozzarella cheese at 151 stations. DNA from chickpeas, a key ingredient in hummus and falafel, was detected on many subway platforms and benches.

The researchers also found bacteria that readily dine on arsenic, sup on oil spills and digest sulfates commonly found in the subways. Some species in the subterranean system are unusually resistant to extremes of acidity, aridity, temperature and radiation.

“They are like New Yorkers,” Dr. Mason said. “They can survive anywhere.”

Additional coverage of the PathoMap Project was also covered by the following outlets:

NPR: What Microbes Lurk In The Subways Of New York? Mysteries Abound

PBS Newshour: Google Maps for Bacteria? How NYC Subway Swab Could Change Public Health

The Washington Post: From Beetles to Bubonic Plague: Bizarre DNA Found in NYC Subway Stations

- CNN: Why Scientists are Studying Germ Universe in N.Y. Subway

CNBC.com: NYC’s Silent Metro Commuters: 562 Species of Bacteria

The New York Times: Among New York Subway’s Millions of Riders, a Study Finds Many Mystery Microbes

- New York Magazine: Scientists Determine Exactly How Disgusting Your Subway Station Is

Time Magazine: DNA Tests Confirm NYC Subway Is a Germaphobe’s Worst Nightmare

UPI: High School Scientists Find Drug-Resistant Bacteria in NYC Subway

Popular Science: Traces of Bubonic Plague and Dysentery Found In New York’s Subway System

The Huffington Post: Top Stories Bubonic Plague And The NYC Subway

Gothamist: A Close Look At The Germs Crawling Around The Subway

Live Science: The Microbes that Ride the NYC Subway with You

Discovery News: Mystery Microbes Among DNA Diversity on NYC Surfaces

WABC-TV: Researchers Map Bacteria In New York City Subway System

WCBS-TV News: ‘PathoMap’ Breaks Down Bacteria, Other Microorganisms At City’s Subway Stations

CBSLocal.com: Nina In New York: The DNA of The MTA Is As Filthy As You’d Expect

CBSNews.com: Dangerous Pathogens and Mystery Microbes Ride The Subway

WNBC News: “PathoMap” Traces Subway Bacteria, Finds DNA Linked to Plague, Sauerkraut

NY 1 News: Study Reveals Wild World of Bacteria in Subway System, DOH Slams Results

Fox 5: Scientists Say Bubonic Plague, Anthrax Remnants on Subways

WPIX 11: Gross Interactive Map Reveals Bacteria Species Living At Each Subway Station

Daily News: More Than 600 Types of Microbes Found On The Subway: Study

- Brooklyn Paper: MetroCurd! Ridge Subway Stations Crawling With Italian Cheese Bacteria

- International Business Times: Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria In Subway Stations