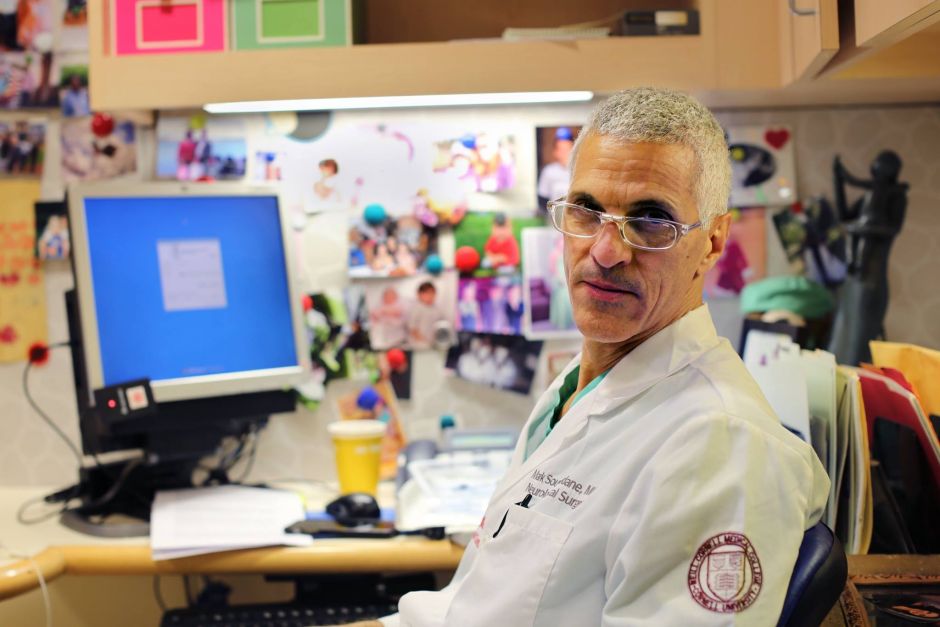

Humans of New York: Mark Souweidane

Pediatric neurosurgeon Mark Souweidane, M.D., of the Weill Cornell Brain and Spine Center and the Children's Brain Tumor Project, was recently featured on the immensely popular Humans of New York blog. Four photos appeared on Facebook, Twitter and the Humans of New York site as part of a series exploring pediatric cancer. The response was overwhelming: hundreds of thousands of viewers, more than 7,000 comments and 18,000 shares.

I’ve been on a mission for seventeen years. It’s my holy grail. I’m trying to cure a brain tumor called DIPG that kills 100 percent of the children who have it. It only affects 200 kids a year so it’s never gotten much attention. But if you saw a child die from DIPG, you’d understand why I care so much. It’s awful. It’s just awful. Parents come to me in droves asking me to help. They say: ‘This can’t happen. Please do something.’ But there’s nothing I can do. Their child will be dead in a year. It’s horrible. It’s been a very tough thing to care about. I didn’t get into neurosurgery to watch kids die. I chose this job to heal people. And DIPG has been seventeen years of watching kids die. It’s a very dark place to work. But if I can find a cure, so much of that pain will be paid back in a single instant. And on that day I will feel like there has been some justice.

When I first started working on DIPG in 1990, I thought: ‘I’ll figure it out in two years.’ That was before I had gray hair. I had no money. My office was the size of a closet and I was buying my own rats. But I was so optimistic. I had no idea what was facing me. There were so many hurdles I didn’t see. Everything was new. I never had any experts I could call or articles I could read. I had to figure everything out on my own. From a surgeon’s viewpoint, the tumor is unforgiving. It infiltrates the brain stem. Everything your body feels or experiences passes through that stem. You can’t violate it with a knife. It’s futile to even think about. So I had to figure out how to insert a catheter through the brain, and inject chemotherapy directly into the tumor. There is zero room for error. These chemicals must only touch the tumor. If you miss the target by a couple millimeters, it can be fatal. Brain surgeons aren’t artists. There isn’t much room to be creative. The innovator in neurosurgery is under a great deal of pressure. We must invent without being too imaginative. If we stray too far from our ancestors, it could lead to death.

In May of 2012, I finally got approval to conduct a clinical trial. A family flew up from Florida with their child Caitlyn. I was so nervous. I’d written so many elegant papers. I’d conducted so many trials on mice. I’d done so many tests in the lab proving that this could work. But here I was looking at a human child. Am I really ready? The spotlight was unbelievable. If I kill this child, it will decimate me emotionally. And the institution’s reputation was on the line. Had I done enough? Had I prepared enough? All these things were running through my mind as Caitlyn’s mother signed the consent. But when she finished, she turned to me and said: ‘Whatever happens, thank you for trying.’ And I still get emotional when I think about that. Because she took so much weight off me. The operation was a success. This is Caitlyn a week later. She could walk! She could jump! She could touch her nose! She lived for a year after that, but then her cancer came back and killed her. It was so hard for me. I was so close to her family. But right now I’ve had about twenty successful trials. That’s twenty living children. One young woman has been alive for three years. Every passing day that those children are still alive is the greatest day of my life.

My childhood was building things: model rockets, model cars, train sets, airplanes. And I didn’t just build them. I focused on every detail. I hand painted every letter on the train. I sanded the wooden ribs of the airplane until everything was so precise and fit. And it felt so good when that work was finished and appreciated. It was the same drive that brought me into neurosurgery. I loved fixing things. And I had always been successful. To get to be a neurosurgeon, I had to succeed on so many levels. I’d become accustomed to success. But I finally found something I couldn’t fix. All my DIPG patients were dying. It was failure beyond failure. Kids were dying because I’m not good enough at this. And they don’t deserve it. And neither do the parents. It’s so hard to face these parents. They’ve envisioned everything that’s going to happen to their child from the day they were born: the first girlfriend, the first job, the first homerun, the first time tasting meatballs, it’s infinite. And they come into my office and, ‘Kaboom.’ All of it disappears. It’s horrible. Seeing their faces. It’s beyond abominable. I just can’t take it. I’ve got to stop these kids from dying.

An affiliated fundraising campaign raised a whopping $3.8 million in two weeks, from 103,000 people.

Photographer Brandon Stanton wrote:

"Dr. Souweidane tells me that this money represents the “single greatest leap forward” in his personal crusade against DIPG."

And the Orlando Sentinel recently featured a story about a fundraiser for another of Souweidane's former patients.