Cancer pill Gleevec keeps patients alive and well for a decade

Everyone hopes and wishes for that last-minute cancer breakthrough that will save doomed patients. It almost never actually happens. With Gleevec, it did.

The once-a-day pill turned chronic myelogenous leukemia, or CML, from a certain death sentence into a manageable disease. Now data shows it's helped 83 percent of patients live 10 years or longer, even with side-effects that include a characteristic rash, nausea and fatigue.

And some may be able to stop taking the pills altogether, even though they are not cured, the original team of researchers reported in the New England Journal of Medicine Thursday.

"It's the first targeted personalized medicine that had ever been used. It was also the most successful," said Dr. Richard Silver, a hematologist and oncologist at New York Presbyterian-Weill Cornell Medical Center who helped first test the drug in patients.

"This has been the thrill of my life," Silver told NBC News.

Before Gleevec hit the market, CML patients had three options: treatment with toxic chemotherapy, a bone marrow transplant, or just dying. Even with treatment, patients rarely lived longer than three years. "It was really a death warrant," Silver said.

Gleevec worked so well and so quickly that the trial testing the drug against the older chemo regimen was stopped so everyone could get the pill. Food and Drug Administration approval was swift and now the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society estimates 36,000 to 100,000 Americans are CML survivors.

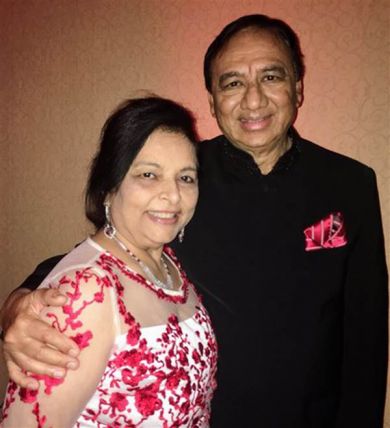

Bharat Shah of Atlanta is one of them.

Shah had brought his wife Milan and his daughter-in-law Dr. Reshma Shah, a family practice physician, to the meeting where his oncologist gave him the diagnosis in 2000. "I looked at Reshma, and as soon as her head went down and she started crying I knew that the news was not good," Shah recounted.

"I had like six months to three years to live."

Shah felt fine, but his blood told a different story. His white blood cells, the immune system cells, were proliferating wildly. Just 60, he faced harsh chemo and all its side-effects before near-certain death.

He and his family hit the Internet. Several relatives are physicians and they heard Silver's lab was taking part in a clinical trial of Gleevec. Through a coincidence, one physician relative met a former staffer of Silver's and Shah enrolled in the trial.

"After 17 years of treatment, the only side-effect that I feel is that my eyes are a little puffy," Shah told NBC News."Within two months I was back to normal," Shah said. He became a regular commuter between Atlanta and New York. He takes Gleevec every day.

He plays golf every week and does charity work. And Silver has him talk to his medical school class every year.

"He might have been dead. It's been unbelievable," said Silver.

"To have lived through the opportunity where we can go to a patient and say, 'We have got this new drug and it looks great' and it is great," Silver added. "You can imagine what a thrill it is to see these people and see them live their lives productively, with their jobs and their families and children and grandchildren."

The researchers, led by Dr. Brian Druker of Oregon Health & Science University, published their final report Thursday on the original Gleevec trial, which had 1,100 patients.

Gleevec is targeted to a mutation specific to CML. Now targeted therapies are common and can have remarkable results in a small group of patients with specific genetic mutations in their tumors. With CML, the same genetic changes affected almost every patient.The drug was the first to be designed to match the particular genetic mutation that causes CML. Up to then, most chemotherapy went after rapidly dividing cells -- a hallmark of cancer, but an approach that also damages hair follicles, the inside of the mouth, the lining of the intestines and other healthy tissue.

"It's a 10-year survival of 83 percent, which is extraordinary," Silver said. "It has led to what we call biologic cures." Patients still have leukemia, but it's not affecting their blood cell counts.

In Europe, doctors are beginning to recommend that patients who are doing well on the drug for a year or longer try stopping. Druker and colleagues believe that about 10 percent of all Gleevec patients will be able to safely stop taking the drug, and 40 percent or more of those who show a quick response to the drug.

Shah tried stopping, but his blood count soon shot up and he and Silver decided he should resume the pills.

It's not all sweetness and light. Even though Gleevec has been on the market for more than 15 years, it still costs more than $140,000 a year, according to Dr. Hagop Kantarjian of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, one of the original Gleevec trial leaders.

Shah, now on Medicare, pays for his own travel to and from New York to see Silver and follow up on his care. "Without insurance, it would have cost me like $20,000 a month," he said. Even so, he spends $8,000 to $10,000 out of pocket for the drug. "Medicare is paying a lot of money on my behalf," Shah said.

Gleevec, known generically as imatinib, now has generic rivals. The price is not down in the U.S. yet but the pills made by one Indian generic company cost $400 a year and a Canadian version costs $8,800, Kantarjian wrote in a review for the American Society for Clinical Oncology.

"Imatinib was priced at $26,000 a year in 2001. The price of imatinib has increased by 10 percent to 20 percent annually," he noted.

Oncologists have been pressuring Gleevec's maker, Novartis, and generic makers to bring the price down.