Old drug may provide new hope to melanoma patients

A drug once used to treat diabetes may be of big benefit to skin cancer patients.

The treatment of choice for Type 2 diabetes prior to the introduction of metformin, phenformin was taken off the market in 1978 due to concerns about toxicity – it heightened the risk of a fatal buildup of lactate in the body (lactic acidosis). However, phenformin has shown promise as an anti-melanoma therapy where metformin has failed.

Researchers from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center have filed a request with the FDA to bring back the drug phenformin as a therapeutic for melanoma and are teaming up with researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine and Massachusetts General Hospital to conduct the first clinical trials.

Scientists believe phenformin could be safely repurposed as part of an established combination treatment for the most common form of melanoma -- and as a part of a therapy for less common forms of the disease that currently have no effective treatment.

The most important signaling pathway in melanoma is the MAP Kinase (MAPK) cascade. When proteins in this signaling chain are mutated, they can become stuck in the “on” position, resulting in uncontrolled proliferation and tumor growth. The standard treatment for the most common form of melanoma, which is caused by mutations in the BRAF gene (approximately half of all melanoma cases), is a combination of drugs targeting the BRAF and MEK proteins of the MAP Kinase cascade.

BRAF and MEK inhibitors curb tumor growth in patients with BRAF mutation. However, most patients develop resistance to these drugs during the course of treatment, leading researchers to seek additional options.

Inhibiting growth

In 2013, cancer metabolism expert Lewis Cantley, Ph.D., director of the Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Bin Zheng Ph.D., his former-postdoc who is now an assistant professor at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, found that phenformin worked synergistically with melanoma drugs to kill BRAF-mutated cancer cells and inhibit the emergence of resistant clones.

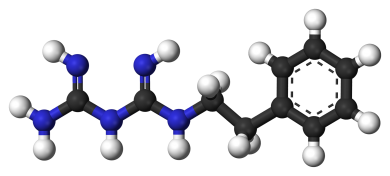

As a biguanide, phenformin inhibits energy production in the cell, leading to activation of AMPK. AMPK alters cellular metabolism and directly inhibits the MAPK pathway.

“Phenformin acts as an energy brake, and reprograms proliferative cancer metabolism to catabolism,” Cantley said.

Both metformin and phenformin are biguanides with similar mechanisms of action. But the two drugs differ in potency. Metformin is functional in the liver, whereas phenformin is able to get into cells easily and can affect many types of cells, thereby making it much more effective – at a lower dose – for treating cancer.

“Early preclinical results strongly suggest that significant therapeutic advantage may be achieved by combining AMPK activators such as phenformin with BRAF and MEK inhibitors for the treatment of melanoma,” Cantley said.

So Cantley has teamed up with Zheng, Weill Cornell colleague Jonathan Zippin, M.D., Ph.D., Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center researchers Craig Thompson, M.D., and Paul Chapman M.D., and Massachusetts General Hospital researchers Keith Flaherty, M.D., and Ryan Sullivan, M.D., to begin a clinical trial testing the combination in human patients.

They appealed to the FDA to use the drug in melanoma patients as part of a Phase Ib trial to test the drug’s toxicity and begin to establish doses that are both safe and effective. Patients who respond well to the drug will then move on to a dose escalation phase, during which Dr. Zippin will track tumor activity and treatment responses to identify potential biomarkers.

Activating hope

While the current trial will focus on patients with BRAF mutations, Dr. Zippin believes phenformin may also provide hope for patients with melanoma driven by other mutations.

Similar to BRAF mutations, loss of function of the NF1 gene activates the MAP Kinase signaling pathway. NF1 loss leads to hyper-activated Ras and AKT signaling, causing proliferation of cancer cells.

Patients with mutations in their NF1 gene – which account for about 14 percent of those with melanoma, and a majority of those with uveal (eye) melanoma – do not respond to BRAF/MEK therapy; preclinical studies have suggested that drugs inhibiting ERK would likely provide benefit, but the doses required would be too toxic.

In a study published online Jan. 28 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, Drs. Zheng and Zippin showed that combining phenformin with ERK inhibitors synergistically killed NF1 mutant melanomas, allowing for the use of ERK inhibitors at potentially more tolerable doses.

“The combination of ERK inhibitor and phenformin showed potent synergy, and cooperatively induced apoptosis (cell death),” Dr. Zippin said. “Phenformin allowed us to use a lot less of the ERK inhibitor drug, reducing toxicity and making the combination treatment a potential option for these patients.”

The work was supported by a Melanoma Research Alliance Team Science Award and grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Harry J. Lloyd Charitable Trust, Clinique Clinical Scholars Award, Dermatology Foundation and the American Skin Association.

Dr. Cantley serves on the Board of Directors of Agios Pharmaceuticals and the Scientific Advisory Board of Enlibrium, companies developing drugs that target cancer metabolism. He is also founder of Petra Pharma Corporation, a company developing small molecule inhibitors for the treatment of cancer and metabolic diseases. Dr. Zippin is the co-founder of CEP Biotech, a company that is commercializing early diagnostics for various dermatological and clinical conditions. He is also an advisor with equity in the company YouVLabs, the makers of wearable technology to measure accurately solar ultraviolet radiation.