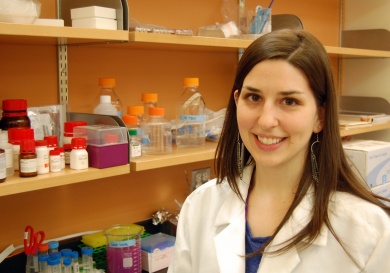

Graduate student has cultured an unexpected side passion: Fish

In the course of trying to contribute to cures for cancer, Sara DiNapoli has cultured an unexpected side passion: Fish.

The tiny zebrafish has been a big boon to the young scientist as she attempts to elucidate the role of polycomb group proteins in melanoma. Zebrafish is the model organism of choice in the lab of DiNapoli’s mentor, Yariv Houvras, assistant professor of medicine in the Department of Surgery, where she works as a Ph.D. student.

Often used by researchers who study development because of the transparency of its rapidly developing embryos and its regenerative abilities, the zebrafish is also becoming increasingly popular among those investigating diseases like cancer. Embryos engineered to exhibit specific cancer phenotypes can be easily exposed to chemicals or other environmental stimuli to test responses.

“I didn’t really know much about zebrafish before I started. There are so many advantages to using the model, and I think it’s really incredible,” DiNapoli said.

DiNapoli works with transgenic fish that have been modified to express BRAF-V600E, a mutation found in human melanoma, as well as a mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor protein. She uses microinjection of embryos at the one-cell stage to alter gene expression as she explores the regulation of chromatin structure.

In particular, she is trying to tease out the functions of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), a group of proteins that contributes to chromatin compaction and catalyzes the methylation of histone H3 at lysine 27. PRC2 is involved in various biological processes, including differentiation, maintaining cell identity and proliferation, and stem-cell plasticity. The complex is also altered in many types of human cancers.

“There seem to be both gain and loss of function alterations in melanoma, and it’s not clear what the function of PRC2 in melanoma is,” DiNapoli said.

DiNapoli, who attained her BA in biology at New York University in 2011 and expects to complete her Ph.D. in pharmacology in 2017, said her Weill Cornell experience is nothing like she thought it would be.

“In many ways, it’s so much better. The freedom to study what you think is important and interesting, to be able to test a hypothesis and see if it’s correct, it’s something that you don’t get to really experience in classes,” DiNapoli said. “I love coming to work every day. I never know what I might learn and discover, but it’s always exciting.”

DiNapoli shares that enthusiasm with her peers and potential protégées. She is actively involved with the Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences and its Outreach Committee, which aims to engage local youth through school visits and science activities.

The Long Island native said she was encouraged to enter the field by an inspiring high school biology teacher, and she wants to do the same for others.

“She told me: ‘Things that people know today will be really different from what people will know 10 years from now. You can potentially change what’s known.’ That’s very exciting, and not the case in many other fields,” DiNapoli said. “It’s very rewarding to show other people how fun science is.”

DiNapoli said she loves the nurturing network she has tapped into, both within the Houvras lab and among the wider community.

“Dr. Houvras is a great mentor. He’s very accessible, and everyone in the lab is willing to help. As a student, it’s amazing,” DiNapoli said.

The Houvras Lab meets regularly with members of seven other labs at Weill, Memorial Sloan Kettering and Rockefeller University, who form a small tri-institutional zebrafish community.

“We share reagents, tools and technology. And we learn a lot from each other, even if the focus of our research is different,” DiNapoli said. “There’s so much science going on here, and the collaborations are always rewarding.”