Contributing to an international cancer corps

Radiation therapy provides many benefits to breast cancer patients: relieving symptoms, eliminating tumors, preventing recurrence, and, in some cases, avoiding disfiguring surgery.

Unless you live in Armenia.

Or Nicaragua.

Or Mali.

Or dozens of other low and middle-income countries around the world, where access to such therapy is limited or non-existent.

Onyinye Balogun, M.D. is hoping to dampen this disparity by partnering with the International Cancer Expert Corps (ICEC) to create a Weill Cornell Medicine hub of global outreach for cancer care -- one that will incorporate radiation therapy and multiple other specialties including palliative care, medical oncology and surgery.

Founded in 2013, ICEC’s goal is to establish and build sustainable cancer programs that function at world-class standards, by providing training and mentoring of healthcare providers to deliver resource-appropriate cancer care in resource-poor settings, where three-quarters of cancer deaths occur. Weill Cornell Medicine physicians Dattrayedu Nori M.D., Silvia Formenti, M.D. and Harmar Brereton, M.D are also involved in the effort, with Formenti and Brereton serving as ICEC board members.

“Radiation is one of the pillars of cancer care, but it is often overlooked in international work,” Balogun said. “More than half of all cancer patients require radiotherapy at some stage during their illness. We need to incorporate it if there is any hope of a cure for some of these cancers. It can also can be a vital element of palliative care.”

Although the incidence of breast cancer is still highest in developed countries, women in developing nations are disproportionately dying as a result of the disease. Or losing breasts that might have been spared because of lack of access to reliable radiation treatment. Even those few women who are lucky enough to live close to a radiation center may encounter broken-down equipment, or staff who are not trained to deliver the optimal therapy. They may not be able to afford the costs of travel, or the hospital stays required to minimize missed treatments since prolonging treatment regimens could have a significant adverse impact on disease control and survival. Also, many of the women – who tend to be younger than their US counterparts – face additional cultural pressures.

“I don’t think a woman should have to lose her breasts. We should be able to find a way to bring the advancements that we enjoy to developing countries,” Balogun said.

Bounding over barriers

The assistant professor of radiation oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine has seen first-hand the barriers that breast cancer patients face in low and middle-income countries.

Balogun was inspired to become a radiation oncologist at the tender age of 13, after witnessing her aunt’s breast cancer treatment in Nigeria – and the radiation burns she suffered as a result.

More recently, she traveled to Armenia to study its systems, make recommendations for improvement, and implement a curriculum for staff to make the most of their newly purchased equipment at the National Center of Oncology, the country’s main radiotherapy-equipped center.

She is now setting her sights on Gabon, to develop a long-term relationship with its principal cancer center and she is recruiting a multidisciplinary team of faculty and community physicians across the oncology spectrum to act as consultants and mentors. Together, they will set up immediate improvements that are then sustained through regular check-ins and long-distance telecommunication.

“We are hoping to draw upon our expertise in surgical oncology, medical oncology, gynecological oncology and radiation oncology to be a force to do good globally,” Balogun said. “We are doing a good job here, but we are closing our eyes to the fire that’s being lit under us around the world.”

By the numbers

To do so will take both resources and creativity.

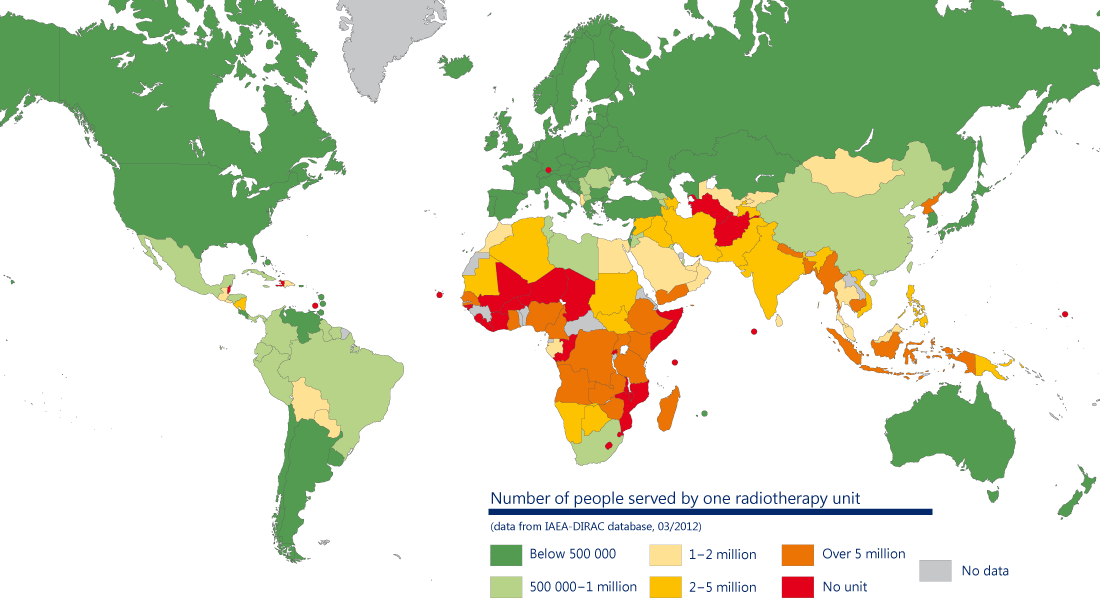

The first big barrier is technology. With an estimated shortage of about 5,000 radiotherapy machines, 70 percent of cancer patients living in lower and middle-income countries cannot benefit from this essential curative or pain relieving treatment. The problem is most severe in sub Saharan Africa, where 80 percent of the continent’s one billion inhabitants live without proper access to basic radiotherapy and related cancer services, and where only 20 percent of patients survive cancers, such as cervical cancer, that are highly curable elsewhere in the world.

In most high-income countries, at least one radiotherapy machine is available for every 250,000 people. In contrast, in nearly 20 lower and middle-income countries, only one machine is available for over 5 million people. Of 139 lower and middle-income countries, 55 (39.5%) have no radiation therapy facilities at all.

Part of the problem is the cost of acquiring, running and maintaining modern radiation therapy machines. ICEC is working with manufacturers to try to overcome some of these barriers.

In a 2015 report prepared with Formenti, Balogun admitted that even with the optimal amount of equipment, radiation therapy might still prove unaffordable for many.

“Decision-analytic models estimate that post-mastectomy radiation therapy costs $12,000–$22,600 per QALY (quality-adjusted life-year). Although this is cost-effective for most upper-middle-income countries, it is unlikely to be sustainable for low to lower-middle-income countries,” Balogun wrote.

And of course, having technology means nothing without well-trained staff to use it.

There is an enormous need for trained medical physicists, radiation therapists and oncologists in lower and middle-income countries. In one analysis, Gabon would need 44 additional machines, 128 radiation therapists, 79 radiation oncologists and 43 physicists to bring it up to recommended levels. A report by the International Atomic Energy Agency estimated that more than 12,000 radiation oncologists will be needed by 2020 to staff radiation therapy facilities in lower and middle-income nations.

Balogun is doing what she can to address such challenges by thinking creatively about how to divide up the tasks that need to be done in an oncology unit, and how to alter treatments to save time and costs.

Simplifying the radiation therapy planning process and training nurses and radiation therapists to undertake more of the patient preparation, for instance, could provide a valuable time-saving feature in developing countries with a limited number of physicians.

Shortening chemotherapy and radiation therapy courses could reduce costs and make treatment more convenient to patients, decreasing the time they need to be away from home, Balogun said. Strategies could include hypofractionated breast radiotherapy or concurrent chemoradiation therapy, which are commonly used in the United States.

The impact would be far reaching, she said.

“Cancer kills more than HIV, TB and malaria combined, and the burden is increasingly falling on low- and middle-income countries,” Balogun said. “This impacts not only the lives of patients and their families, but entire communities, because of its huge physical, emotional, and financial toll.”