Review: Twin Books on the Genome, Far From Identical

This is an excerpt of a review that appeared in the New York Times. Read the original here.

Twins born minutes apart may be eerily similar or just as eerily different. Even if they are not identical, they share yards of genetic material, and yet one turns out large and one small, one strong and one weak, one a poet and the other a mumbler.

We see these disparities in people all the time. And now we see them in a pair of books on the gene, published on the same day. Sharing yards of genetic material, both works aim to explain the power and mystery of the human genome, yet could not be more different.

...

A cancer physician at Columbia University, Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee dazzled readers with his Pulitzer-winning “The Emperor of All Maladies” in 2010. That achievement was evidently just a warm-up for his virtuoso performance in “The Gene: An Intimate History,” in which he braids science, history and memoir into an epic with all the range and biblical thunder of “Paradise Lost.” (Read an excerpt.)

...

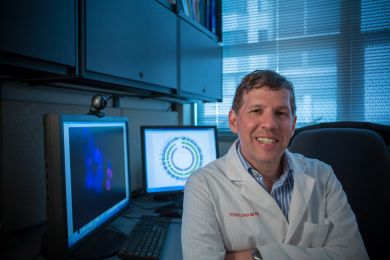

Dr. Steven Lipkin lacks Dr. Mukherjee’s skills; even with a co-author, he struggles mightily in “The Age of Genomes: Tales From the Front Lines of Genetic Medicine” to explain the scientific concepts underlying his work. What Dr. Lipkin does have are patients. (Read an excerpt.)

A clinical geneticist in New York City, he is among those charged with translating complicated principles into viable medical practice. In his work, Dr. Lipkin meets patients like “Lydia,” who worries that because she looks like her mother she is fated to die young of the same ovarian cancer.

There is “Samantha,” who suffers from a dire genetic syndrome that precludes safe pregnancy. There is “Sean,” a surfer dude with a relatively mild genetic condition that is ruining his sex life.

As in the rest of clinical medicine, though, nothing is entirely predictable for these patients. Lydia is relieved to hear she has little chance of developing her mother’s cancer, but expresses exactly zero interest in knowing more about her father’s early Alzheimer’s disease, a far more heritable condition.

Samantha would routinely be advised to avoid pregnancy at all costs, save for one small detail: She shows up for her first appointment with a healthy baby boy on one knee. Her one uneventful pregnancy complicates decision making about subsequent ones.

As for Sean, a honed state-of-the-art treatment to prop up his mutant genes is available. Unfortunately, it is very expensive, and he is uninsured.

Insurance is a scientific concept that Dr. Mukherjee does not include in his glorious tour of human genetics, but it governs the work of clinicians who must plead, bargain and appeal for indicated tests and treatments to be approved. The society that rewrites the genetic code, as Dr. Lipkin points out, is likely to become one in which the very expensive tools of genetic medicine forge yet one more barrier between rich and poor.

When Dr. Lipkin sequences his own genome, he runs into another feature of the landscape Dr. Mukherjee overlooks: the proliferation of cut-rate, poorly standardized services out there. Dr. Lipkin first springs for a cheap genotype and gets what he pays for in the form of a syndrome he knows perfectly well he doesn’t have. A better test corrects the error.

These stories from the trenches make it clear that the clinical genetics will not be spared the misery-inducing features of the rest of medicine, in which the reigning slogan is “caveat emptor.”

Let the poet sing his long, lovely epic; it is still the harried, inarticulate, much beleaguered guy in the white coat who will be cementing the transactions.